OEUVRE

Social Commentary

in the art of

Renee Radell

Post-War Contemporary artist Renee Radell’s social commentary art of the 1960s and 1970s, was her unique politically charged version of earlier Social Realism and American Figurative Expressionism in American painting. The Vietnam war era was a time of widespread protest art and activist art. Radell too expressed deep concern for societal strife in her then contemporary painting. Her visceral social commentary statements addressed racial tensions, the horrors of war and political machinations.

It was also a time when the young mother of five from Michigan painted with great sensitivity her reflections on Americana family life with shades of religious beliefs.

This juxtaposition of the horror of war art and the peace of family, painted through the lens of a consummate colorist with stellar studio technique, caused universal praise in the press among art critics in a consistent stream of art reviews.

Renee Radell Web of Circumstance

By way of illustration, in an excerpt from her recent monograph on Renee Radell, award winning author and art critic Eleanor Heartney explains with scholarly precision the power, excitement and meaning that Renee Radell expressed in her social commentary art of that era.

“Throughout the sixties and seventies, Radell was painting in rural Michigan, but, as the works above demonstrate, she absorbed the turmoil of the time. The struggle for civil rights, the assassinations of progressive social and political leaders, the growing disaster of the Vietnam War, the youth revolt and the backlash against protest at home all found their way into her paintings. This period sees some of her most trenchant political and social commentary and also coincides with her growing visibility in New York.

The works that gained Radell this notice include a number of pictures that comment directly on the political confusion of the time. This was a period when the mainstream art world was immersed in the transition from Abstract Expressionism to Pop and Minimalism. Conventional narrative has tended to downplay the importance of the strain of social commentary in American art that stretches back to Ben Shahn, Isobel Bishop, and Raphael Soyer in the 1930s and continued on in the 1960s in the work of artists like Mauricio Lasansky, Leonard Baskin and Leon Golub. Radell’s works of the 1960s and 70s belong to this lineage. She fearlessly took on the issues of the day, presenting them with the penetrating vision that exposes and skewers hypocrisy, whether it appears on the left or the right.

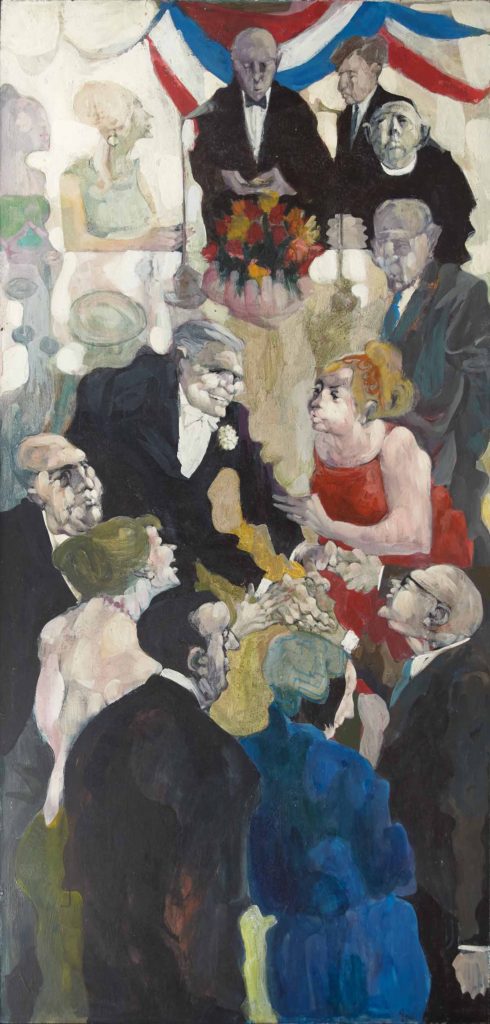

Political Fertility Rite (1965) for instance, is a dissection of the workings of the political process within the broader context of human machinations. Centered around a figure who very much resembles George Romney, then campaigning for the Republican Presidential nomination, a glad-handing politician at a hall swathed with the American Flag works a crowd that includes funders, socialites, business people and clergymen. In the words of Arts Magazine critic Cindy Nemser who reviewed Radell’s exhibition in November 1967, “These are not symbols of evil and corruption. They are human beings, caught in a web from which they cannot extricate themselves. They play their assigned parts in a meaningless comedy that goes on eternally.”

“. . . with Liberty and Justice for All” (1968) presents the darker undercurrents that such political spectacles obscure. Inspired by the hopes dashed by Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, it offers a picture of America that touches on racial disparity, middle class complacency, and youthful idealism. Floating balloons symbolize the hopes of the American dream adrift while the viewer is invited to participate with a mirror glued to the picture serving as its own balloon. H. G. Landon, writing in Park East Magazine in March 1969, noted that this work “epitomizes all the poignancy and grief resulting from the tragedy of Kennedy’s untimely death. Here are the disadvantaged, the young – all those to whom he provided inspiration – as they continue in their search for a better world. This painting includes an exit sign, the stars and stripes and even a bit of space; it is an almost overwhelming opus.”

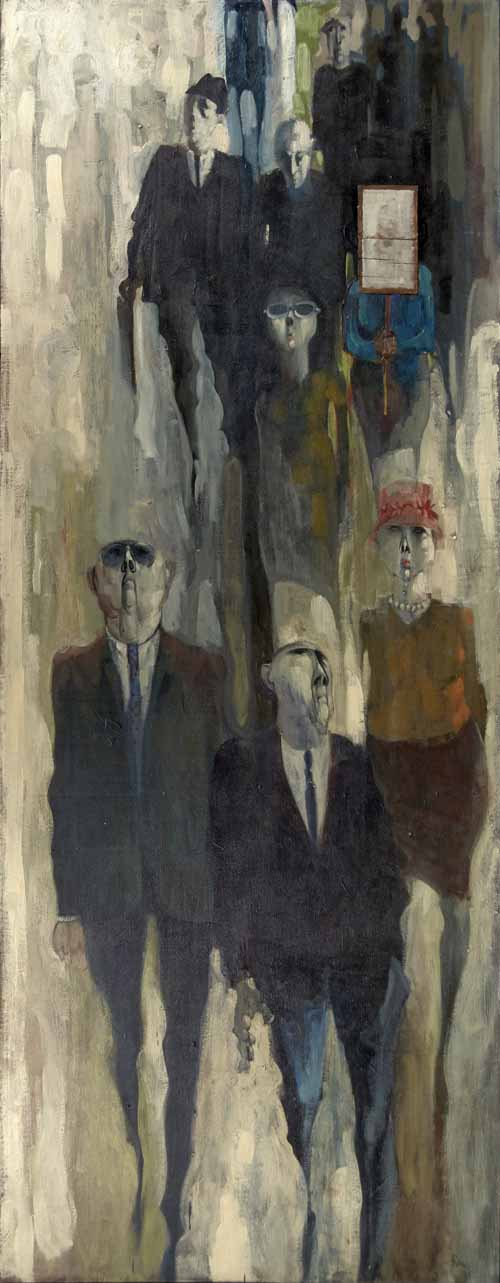

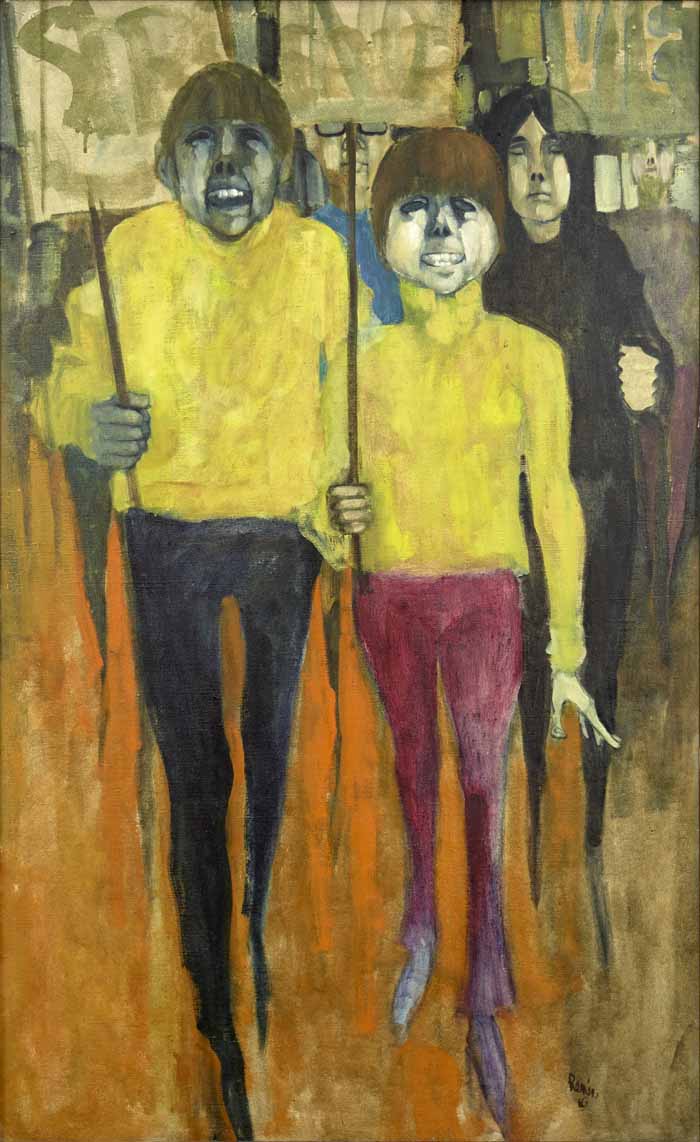

“Where’s Marlboro Country? (1966) addresses the misguided justifications that surrounded the ever-escalating Vietnam War. In an evocation of the biblical injunction against willful ignorance, Radell composes a parade of folly, as complacent Americans regimentally follow a blind leader toward the mythical America epitomized by the national billboard fantasy of Marlboro Country. Nor did Radell spare those who jumped on the protest bandwagon for their own selfish purposes. Doing Their Thing, from 1974, takes a dim view of youthful agitators who, as Russell Kirk noted in his Detroit News Magazine essay, “protest violently against the very affluent society which produced them.”

Radell’s measured explorations of social pathologies touched a nerve in the troubled 60s. As Marlene Zucker noted in her 1967 Art News article “Renee Radell is not a Surrealist, but in her souped-up realism is the ritual unemployment of a dream. She sustains a stern psychological undertow. Her people are drawing, unprepared, pregnant, grabbing for power-flowers, privileged, then let go.”

As the war ground on, Radell’s commentaries became ever more direct. Profit of War (1966, plate_) presents a ravaged mother clasping the body of her dead child. The work brings to mind at once Renaissance depictions of the deposition of Christ, and the tragic war victims of German artist Kathe Kollwitz, blending them to create a timeless image of the waste of war. On a similar note, Hero in Death (1964, plate_) recalls the assassination of John F. Kennedy, presenting another timeless image, this time of an anguished corpse stretched out on the ground. Radell reminds us that the anonymous deaths of soldiers and civilians in wartime are no less tragic than those of famous politicians.

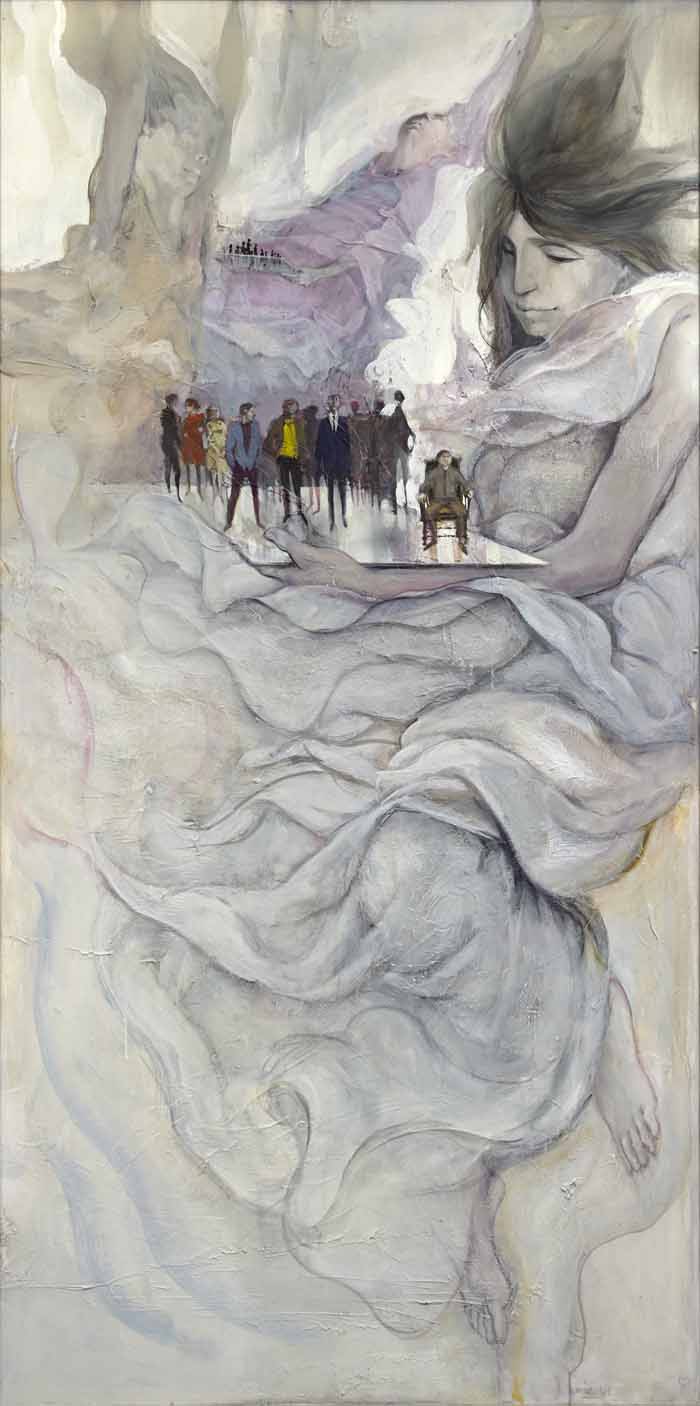

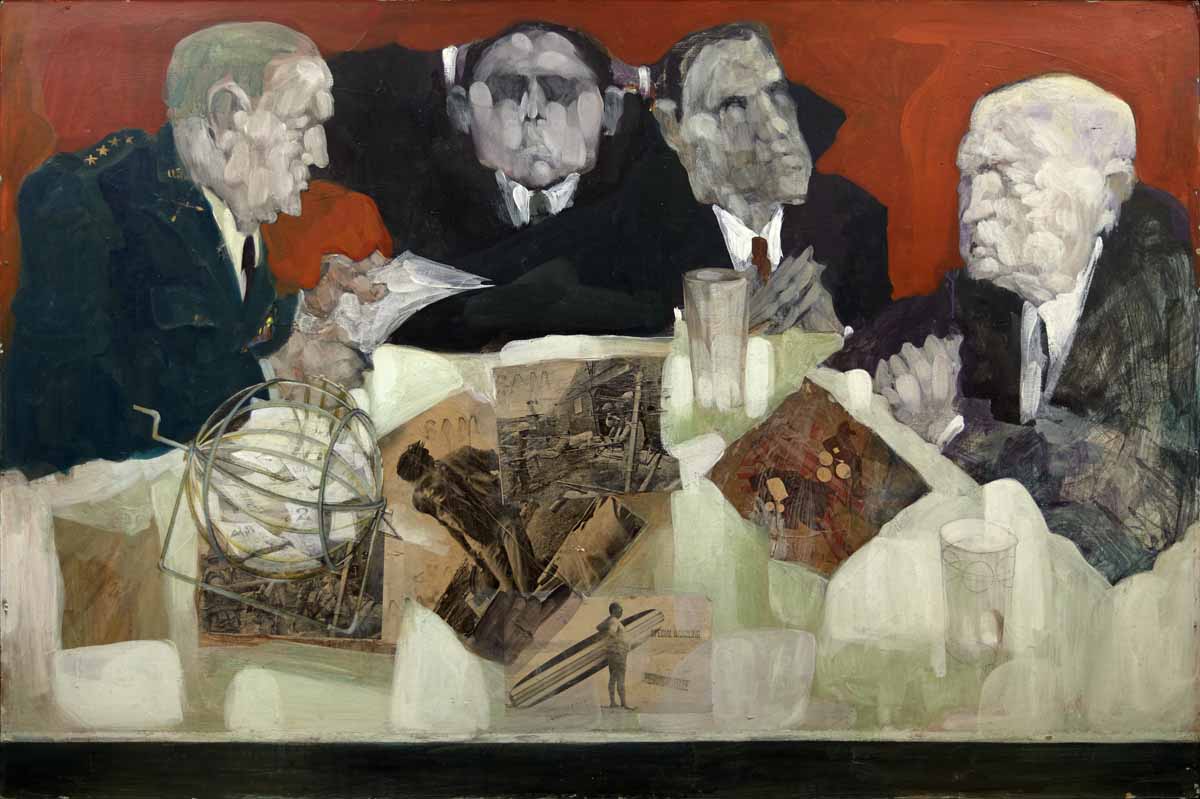

Other works lay bare the societal chasms that opened up during the Vietnam era between those who remained comfortably at home and those who went to war, and between those who made the decisions and those who were designated to carry them out. Commitment Committee (1972) is a commentary on the infamous draft lottery that determined young men’s fates during the final years of the War. Mixing collaged photos and painted images, it presents generals and politicians around a table, spinning the machine that would determine draft eligibility. One photo, stamped “Special Handling”, shows an exempted, portly surfer on a beach somewhere far distant from the mayhem in South East Asia.

Diary of a Commuter (1974) uses the metaphor of the commuter train and the conveyor belt to suggest the very different trajectories of comfortable commuters reading about the War in their train compartments and young men literally being processed for war. In the center, dividing the two, are a mother and daughter, evoking the ambiguous role, in the parlance of the Second World War, of “those who also serve as they stand and wait.” This work, painted at the beginning of the computer era, incorporates a collaged sheet of computer-generated numerals standing in for the anonymous calculations that sent youthful soldiers to their fate. Red numerals indicate a fatality that delivers the soldiers home – in death, bedecked in helmet and uniform, and with rifles at the ready.”